The First World War, known at the time as the Great War, was a truly global conflict. Even on the Western Front, which stretched from the Belgian coast down through France to Alsace, nestling against the Swiss border, it was more than a case of French and British soldiers fighting their German enemy. Troops from all over these countries’ empires, such as India, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, were called up to fight. They are commemorated today across the front, in war cemeteries and on memorials such as Ieper’s famous Menin Gate.

In September, I spent a few days exploring and revisiting parts of the Flanders section of the Western Front, in preparation for some tour guiding work this week. As well as visiting Ieper (perhaps more well known by its Francophile moniker of Ypres, or what the British ‘Tommies’ called it, Wipers), I based myself in Poperinge, a British hub behind the front line.

Flanders saw decisive early fighting in the autumn of 1914, as both sides dug into trenches, their stalemate replacing a race for control of access to the sea as winter crept upon them. Three further battles in the area around the British headquarters as Ieper, in 1915, 1917 and 1918, have left this region pockmarked with reminders of the fighting.

Based at the Talbot House Museum in ‘Pop’, I my journey on foot and by train by a moving trip around some of the biggest and also the less well-known sites of the Great War. These posts are a record of visit, in which I discuss some of the history and context to what I saw and experienced, as well as recording my thoughts and reactions to these first-hand encounters with the ‘war to end all wars’. As events in the Middle East and Ukraine mean bloodshed and conflict are as much part of the early Twenty-First Century as they were at the start of the Twentieth, what I saw in Flanders feels as important today as it did to relatives participating in the first acts of remembrance a hundred years ago.

Because these recordings were made at the sites I talk about, please do excuse some background noise, such as wind, the crunching of leaves or passing traffic. I had to edit a couple of posts because of this, but feel that, where it is not intrusive, it will hopefully give you a more authentic sense of place.

Poperinge was well behind the lines, just over six miles west of Ieper, which is where much of the British Army in Flanders was headquartered. ‘Pop’, as it became known, was therefore comparatively safe for much of the war, although I do stress ‘comparatively’, as it was hit by shells; nowhere on the Western Front could completely escape death and destruction. Soldiers came to ‘Pop’ for relaxation, recuperation and rest and it was soon the party town of the region. Restaurants, the famous Talbot House (about more of which in a later post) and even laundries offered a degree of normality, welcome respite from the horrors of trench warfare.

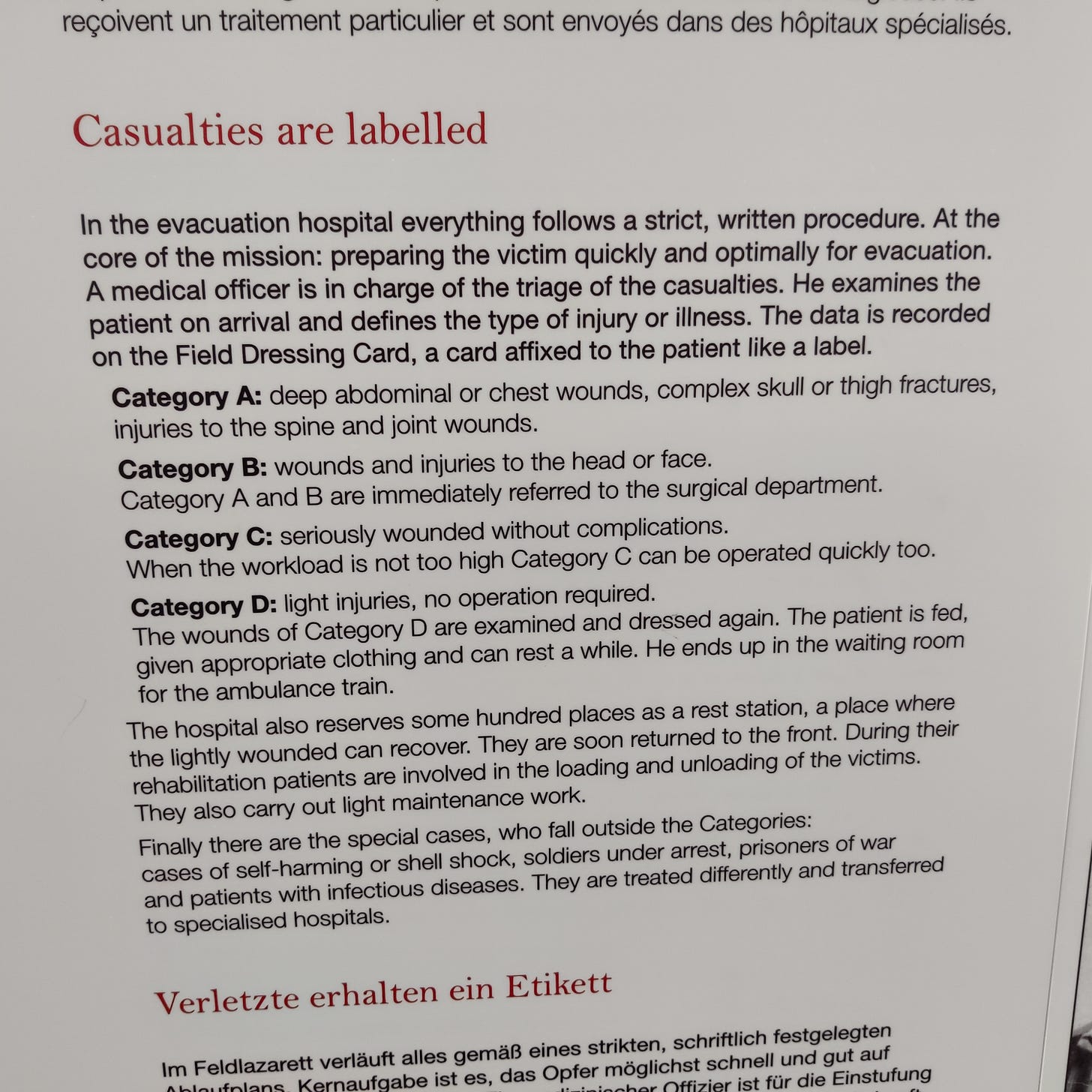

A couple of miles further west lay Lijssenhoek, where a large casualty clearing station grew up in 1915. Usually, injured soldiers would be taken to a dressing station behind the lines, but closer to the action, where immediate, if rudimentary, treatment was given. Triaging would take place and those who needed further intervention would be transferred further back to clearing stations. Here, they might be receive longer-term care or, in many cases, be moved to hospitals back in Britain. Clearing stations were, therefore, often located near railways and an extensive N-gauge model at Lijssenhoek recreates the hub that this site became when, at the time, the line ran further west from Poperinge.

This clip explores the visitor centre at Lijssenhoek, discovering more about its role as a casualty clearing station, the air bases in the surrounding area and the sheer scale of suffering experienced here.

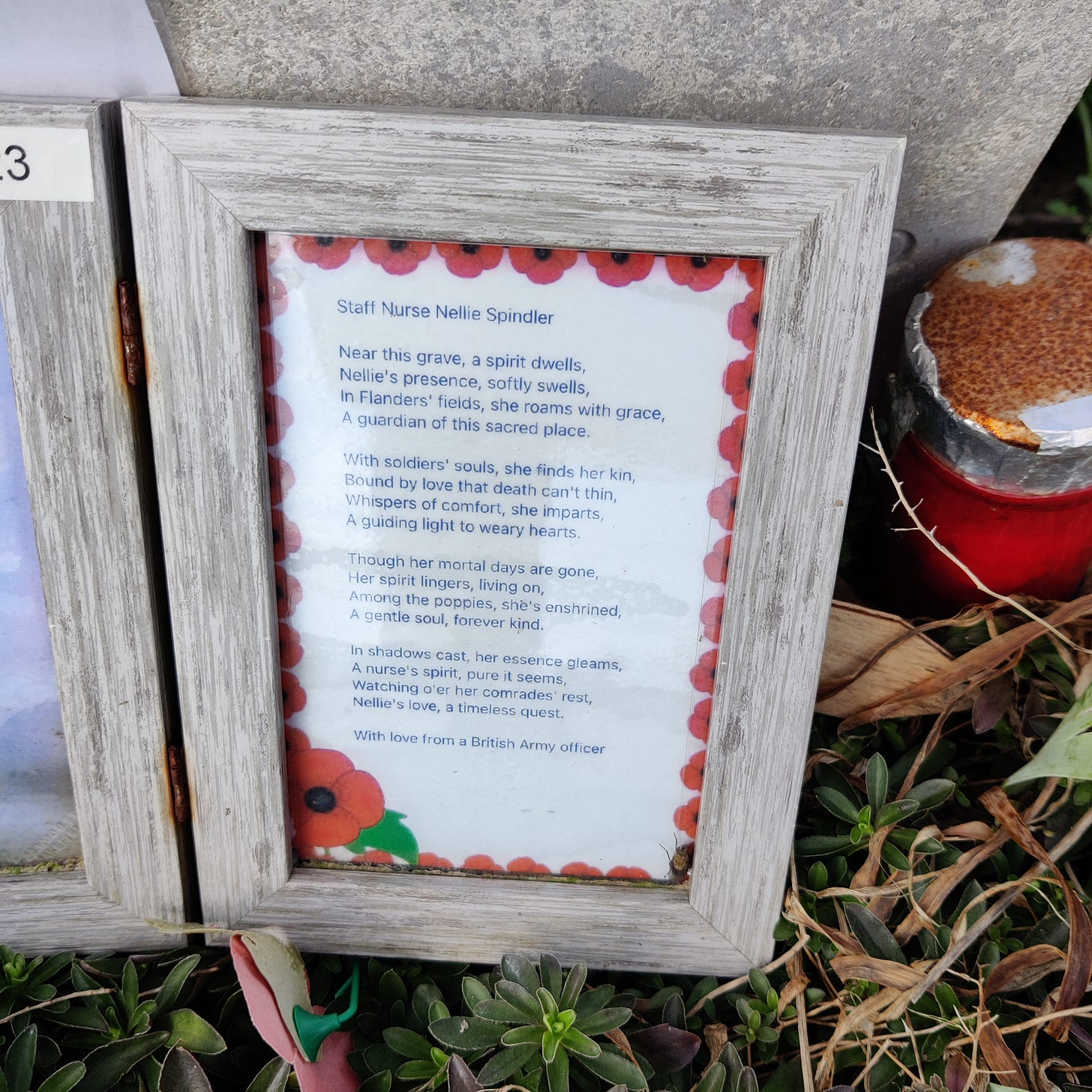

Walking around a windy Lijssenhoek CWGC Cemetery, I reflect on how the practical and emotional aspects of remembrance developed after the war. I think about how cemeteries like Lijssenhoek, of which there are hundreds scattered across the Western Front and beyond, came into being, with their air of tranquility amongst the Portland stone headstones (to correct an error where I refer to them as ‘marble’. Actually, today, replacement or new graves usually use Botticino stone from Italy, which is hardier than Portland). Lijssenhoek contains French graves; France often repatriated its soldiers, or collected bodies into a handful of large, central cemeteries, where it also buried those who could not be identified in mass graves. I saw some German headstones, the ‘enemy’ buried where they fell, showing respect for fellow soldiers as human beings. As a world war, troops from across the globe fought and Lijssenhoek contains Sikh headstones and a number for members of the Chinese Labour Corps, volunteers who did not fight, but undertook essential and dangerous support work, such as the exposed job of digging trenches. Please excuse the sharp edit after I mention these graves, but I had to cut a section because the wind was just too disruptive and would have made my commentary unlistenable.

One grave stands out, that to a young American soldier. The First World War does not haunt the American memory like it does in Europe; the Second and Civil Wars are far more ingrained in the psyche of our allies across the Atlantic. That said, this was the first time American troops had fought on a different continent, arguably playing a decisive role in the last year of the war.

On the road back to Poperinge, I consider the part played by geography in the fighting in Flanders. Mud and poison gas are commonly associated with this stretch of the Western Front.

Later that day, I took the train to Ieper. After dodging into a café to seek refuge from a downpour, appreciating how the weather could transform a low-lying, clay-soiled area notorious for mud, I visited the Menin Gate. It is undergoing extensive restoration work at the moment, but some sections are still accessible and, every evening, the Last Post ceremony is held here (as I will discuss in the second of these posts).

Ieper is a gorgeous, Medieval-seeming town which was the epicentre of the Flanders cloth trade in the Middle Ages. Here I consider its architecture and how German reparations money was used to restore it to its pre-war glory.

In Part 2 of Will Ye Go To Flanders? I will be at the Last Post ceremony, as well as visiting sites in Poperinge and finding out the story of the evocative Talbot House.

Share this post